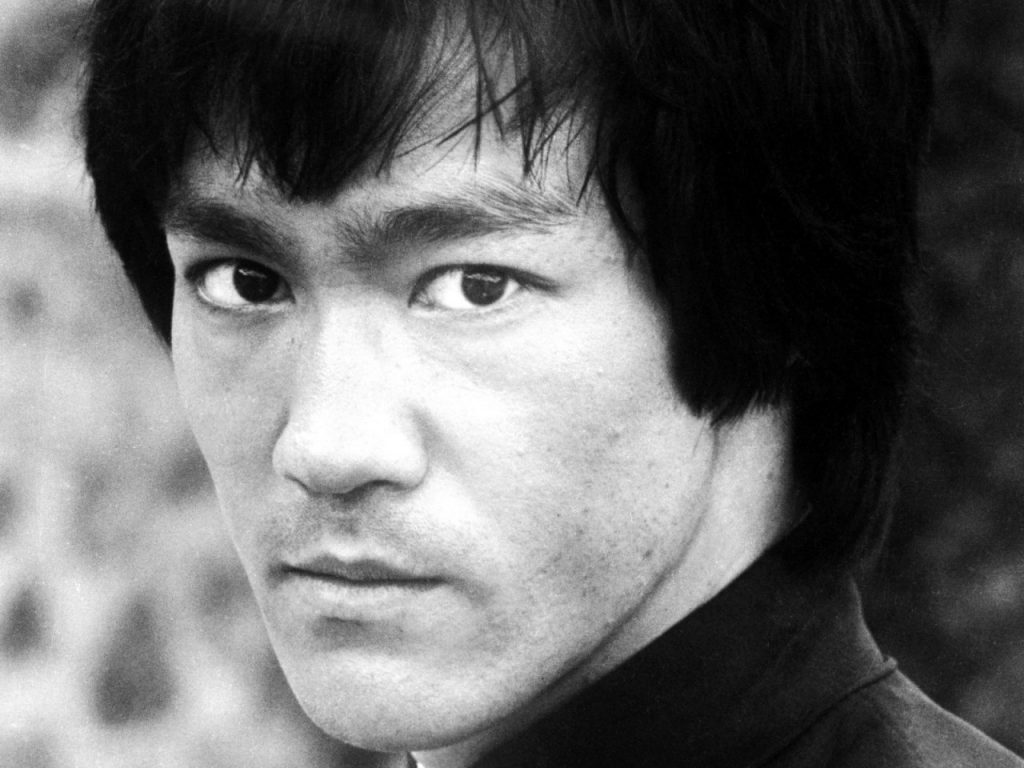

In my last post I wrote about some of the things that Bruce Lee’s martial art of Jeet Kune Do has to offer practitioners of Bartitsu. To be clear, I am not suggesting that Bruce Lee had any knowledge of the articles published by E. W. Barton-Wright, the founder of what we call “canonical Bartitsu”. I do think there are interesting overlaps between elements of each martial art. Bruce Lee spent considerable time studying a number of movement and martial systems to develop his own approach to unarmed combat. His pragmatism and dedication to self-improvement in martial arts can serve as valuable models for current practitioners of Bartitsu and neo-Bartitsu. In this post I will focus on some of Lee’s comments about striking with the hands and feet in his seminal book, Tao of Jeet Kune Do.

Pugilism

In our Bartitsu program we focus on bare-knuckle boxing because it helps us think about how to strike with our hands without using gloves and how to defend against a strike in ways that usually do not involve hard blocks with the arm. For reference, here is Head Instructor David McCormick’s post about some of the approaches we take to pugilism in our school. Lee lists many of the techniques we regularly practice among the “tools of Jeet Kune Do” section of his book. One of his first entries is about the importance of cultivating a good lead punch, which our students know is the first thing we learn in Week 2 of our introductory program. It’s something we return to every time we practice boxing, as Lee notes: “the master of attack must know the value of a straight lead ” (p. 72). It takes time to develop an effective, explosive straight lead punch that utilizes your entire body and makes use of the lunging step with the lead leg. The effort is well worth it. Here are some of Lee’s comments on the lead punch:

- The leading straight punch is the backbone of all punching in Jeet Kune Do. It is used both as an offensive and defensive weapon to “stop” and “intercept” an opponent’s complex attack at a moment’s notice (p. 89).

- The leading straight punch is delivered from your ready stance without any added motions like drawing your hand back to your hip or shoulder (p. 90).

- Relaxation is essential for faster and more powerful punching. Let your lead punch shoot out loosely and easily (p. 90).

- When advancing to attack, the lead foot should not land before the fist makes contact or the body weight will end up on the floor instead of behind the punch. Remember to take up power from the ground by pushing off with the rear foot (p. 90). (He makes this point again on page 97, in italics: in all hand techniques, the hand moves first, preceding the foot. Keep this in mind -- hand before foot -- always).

More experienced Bartitisu students will recognize Lee’s comments that the lead punch can be used for both offensive and defensive purposes. It is unclear, however, whether or not Bruce Lee was advocating that every lead punch should include a step forward, although JKD certainly emphasizes taking the fight to the opponent. In our class, the mechanics of the jab and the lead punch are the same, with the only difference being that the lead punch includes an advancing step that allows one to cover more distance. I suspect Lee was using the term “lead” to refer both to the advancing and to the stationary versions. I was also quite interested to read Lee’s comments about “the elusive lead”; he advocates varying the head position when delivering the lead to keep one’s opponent off balance.

Savate

Part of what prompted this series was the pleasant surprise of flipping to the “tools” section of Tao of Jeet Kune Do to find comments on Savate. I first learned about Savate when I took our beginner’s program a few years ago, and it was interesting to see it referenced when revisiting Lee’s work. I suppose you could say that he knowledge I’ve gained in class over the last few years has given me a new appreciation for the book.

We begin our Savate curriculum with the low kick (coup de pied bas) and the defence against the low kick. We return to these ideas every time we practice Savate, because the low kick is surprising and effective, and because our core defence against this kick is a good defence against most other kicks as well. Lee refers to our low kick as the “cross stomp” (p. 85) and pairs it together with what we would call a side kick and what he calls “the leading shin/knee side kick”. More experienced Bartitsu students will recognize that pairing these two kicks calls attention to the fact that the low kick is made “toes out” to strike the opponent’s lead leg, while the side kick is made “toes in” to strike the opponent’s lead leg. There are some important mechanical differences between the kicks, however: the low kick is more difficult to for your opponent to see coming whereas the side kick requires one to prepare more visibly by raising the lead leg.

The pages that deal with kicking contain a number of Lee’s diagrams about kicking dynamics and how to target one’s strikes. There is a page on Savate (p. 78) that clearly mentions the coup de Savate and emphasizes the heel as a striking point. Bartitsu students who have earned their Blue Sash should also take note of Lee’s comments about Savate’s front (purring) kick: It needs to be “as strategic as a boxer’s cross” (p. 78). Here are some of Lee’s other comments about kicking:

- Kicks that cover a longer distance are used to either reach an opponent that is slightly out of range or to bridge the gap for another technique.

- Kicks should be combined with all phases of footwork: advances, retreats, circling left and right, and parallel moving.

- Lee breaks up the phases of a kick into “initiation, transition, landing, and recovery” and has a few comments on each component. I will need to think more about these ideas before commenting.

- All [kicks] should be done with speed and sudden economy in mind, as well as with power. Learn the most efficient bridging of distance, plus efficient timing with the opponent’s movement (p. 84).

One consistent message in Tao of Jeet Kune Do is the importance of experimenting with martial tools frequently so that you have a good sense of reach, timing, power, and how to work with opponents of different sizes. Regular practice is essential. Academie Duello’s Maestro Devon Boorman has an excellent post on practice that is well worth re-reading. I invite all current Bartitsu students -- and interested newcomers -- to consider some of the lessons of Jeet Kune Do to their martial practices.

References

Lee, Bruce. 1994. Tao of Jeet Kune Do. Santa Clara, CA: Ohara Publications, Incorporated.