One of the most precious resources we have as martial artists is personal 'free time'. We never seem to have enough of it to do the things we ‘want’ to do.

So is it inevitable that we will have to face the choice of either reading and studying any of the myriad books and journal items that feature WMA interests or spending that same time in the salle actually trying to learn the art?

There are perhaps two main approaches to ‘book learning’. These two camps can be described using the following examples:

1) In his recent blog post entitled Exercise Your Mind When You Can’t Exercise Your Body, Devon Boorman wrote: “...reading a book on swordplay can expand your theoretical knowledge, challenge your strategic skill set, and inspire you for your next physical training session. So much of martial arts is in your head, so why not exercise your brain directly?” [1]

2) On the other hand we have another Master who presents a differing view: “Sir William Hope, with Scottish candour, certainly warns those who buy or borrow his ‘Scots Fencing Master (1687)’ that they can learn little from books except what he calls scathingly the ‘contemptible ability of posing as expert swordsmen’.” [2]

In my modest opinion, though we may come to an interest in swordplay through movies and television, it is through personal instruction and book reading that we become actual sword fighters.

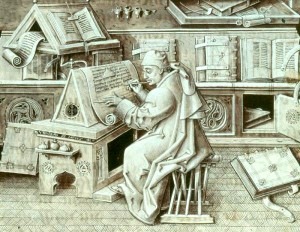

Our Masters have developed their system of instruction to a great degree through their own unique interpretation of their chosen ‘fight book’ of the past. We novices can read to reinforce what we’ve learned in class, and to discover new aspects of the history and technique of the art that we don’t have time to cover on the salle floor. Our developing knowledge of historical sword combat is to a very great degree dependent on books, or written accounts, surviving to modern times … and being studied by people actually physically participate in ‘serious swordplay’.

Reading books put an attractive ‘skin’ of intellectual understanding over the bones and flesh (the drills and techniques) of your day’s lesson.

With that balance between reading and understanding in mind, during these reviews, we’re going to take a look at some of the works available in the Academie Duello library, and try to determine their utility for the modern student of swordplay.

Book Review: "The Sword and the Centuries"

Hutton, A. The Sword and the Centuries, or, Old Sword Days and Old Sword Ways. Grant Richards, London. 1901. 361 pp.

Captain Alfred Hutton (1839-1910) was a ‘garrison soldier’ who believed that sword fighting still had a necessary place in a young officer's education. During Hutton’s service time, British officers actually had to use their blades in combat during skirmishes with various sword-and-speared armed opponents in Asia and Africa.

This is neither a ‘fight book’ nor a syllabus for best use of a sword. In this work, Hutton has collected a variety of examples on the use of the sword during various times and under different circumstances throughout western Europe. Not only does he seek to educate regarding a part of ‘English martial culture’ that has nearly disappeared from history, but he also seeks to entertain, and more importantly, motivate the ‘Albion’ reader to take an interest in a part of their culture too long ignored. For officers specifically, he wrote to convince both those starting their careers as well as established Army Commanders that sword play reinvigorates the fighting spirit and gives one full ‘manly’ attributes (vice academic or mannered ones).

Thirty detailed and passionately written chapters guide us in a short tour of more than four centuries of knights and knaves; lords and louts; and soldiers and soldier-‘wannabes’, all using a variety of side swords and short swords; single swords, clubs and cudgels; rapiers, small swords and falchions; or quarterstaffs and halberds in various combinations. And all to defend their country, lord, honour, pocketbook, drinking prowess, dress sense or even the reputation of a lady – any lady! The examples of course are all taken from the works of others, but in this book we have the advantage of an experienced swordsman giving his comments on how the described event depicted the ‘state of the art’ for the time or contributed to later developments in swordplay.

If you’re looking for an instruction manual on swordplay technique or instruction on how best to hold ‘prima’ with a small sword when facing a halberd, The Sword and the Centuries is not your sort of book. But if you want wonderful ‘historical’ stories of how swordplay came to be and was perfected over time, how your weapon of choice was developed and changed over time to meet new circumstances, and just how swords and sword fighting figured so predominantly in our western European martial, social, military and cultural past, Hutton’s masterpiece is one of the books that all serious students of Western Martial Arts might want to have with them on that mythical ‘deserted island’.

Hutton believed that ‘historical swordplay’ was superior in 'most every way to the ‘sport of fencing’ that we know now as ‘classical or Olympic style’. Be that as it may, we are fortunate as a community that this book -- and Hutton’s concurrent efforts at martial art demonstrations and education -- left us an impressive legacy for this particular way of fighting on which we still build our studies.

I, for one, would have really enjoyed having a beer with this man!

Quotes Out of Context (QOC);

Captain Hutton was very much a Victorian-era, English gentleman, and wrote accordingly.

From the ‘meow!’ files:

“Mr Thomas Killegrew was a gentleman well known at Court for his amorous disposition, but it happened on a time that his heart, or whatever it was that did duty for it, was for the moment disengaged, so he amused it by handing it over to the keeping of Lady Shrewsbury, and she, being in want of some excitement, gave it hospitality; in fact, the pair became very friendly indeed. … He was moreover on intimate terms with the Duke of Buckingham at whose table he was a frequent guest … where he was wont to boast of his success, and to describe the charms of the lady with more zest than discretion. This awoke the curiosity of the Duke, who made up his mind to test the accuracy of Killegrew’s assertions, and he did this in a manner so satisfactory both to the fair one and to himself that the poor young Killegrew’s nose was put completely out of joint … ” p.198-9

And speaking of those that can pull Ponyards from décolletés:

We have and 18-year-old maid known by the moniker ‘Long-Meg’. It seems that in an affair of modest honour – she dressed as a man and effectively took sword and buckler to a mouthy – but noble and well-armed – knight!

“At the first bout Meg hit him on the hand and hurt him a little, but endangered him diverse times, and made him give ground, following so hotly, that she struck Sir James’ weapon out of his hand ; then when she saw him disarmed, she stepped within him, and drawing her Ponyard …” p. 124

1. Boorman, Devon. "Exercise Your Mind When You Can’t Exercise Your Body." Web blog post. News & Blog. Academie Duello. 16 February 2015. Web. 20 Mar 2015.

2. Aylward, J.D. The Small-Sword in England. Hutchinson & Co., London, UK. 1960 p.126