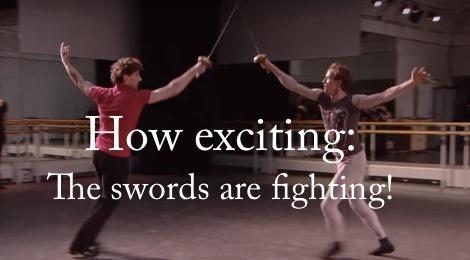

A sword fight is NOT a fight between two swords. Always remember that the two people are fighting to the death, and they're using very effective tools to do so. Otherwise, your fights become dances.

I hope in these clips you can see that most of the time, the actors look like they're choreographed because they're crossing swords in a way that does not look like an intentional attack toward the opponent.

Romeo and Juliet (Royal Ballet)

Star Wars Episode Three

(Click here to see the battle between Anakin and Obi-Wan as embedding on this video is not enabled.)

To make great fights, every attack must seem intended to hit the opponent.

Except....

Gimme A Beat

The beat and changes of engagement can be confusing. The swords hit each other, but neither side is trying to hit the other person. The goal of the beat and all attacks on the blade is to move my opponent's blade out of alignment as a preparation to attack. In other words, it's very hard for me to attack when I've got the bad guy's sword pointed at me. So, the first thing I need to do is get it out of the way so that I can really attack.

On stage, we want the beat to look abrupt and strong. However, I don't want to smash my partner's blade when they're not expecting it, or they might be disarmed unintentionally.

What we're looking for is The Goldilocks Beat: not too heavy, not too light, just stopping at centre. Similar to how we deliver a cut in stage combat, you want to point at your target and arrive precisely there without slowing down. In this case, the target you're aiming for is your opponent's blade. When you touch, your partner could stay put, because the touch will be fast but very light. Instead, the victim will move their sword aside as if you hit them with force. In this way, your point is ready for a subsequent attack, and your partner's sword is out of the line, as if a real beat happened. The stage combat version will not accidentally disarm your partner, or cause damage to the blades.

Try and Try Again

Now, in a real sword fight, there may be many attempts at a beat that fail, so no attack ensued. Perhaps I don't move the opponent's blade far enough out of line, or they take a step so our distance changes, or we both try to beat at the same time. If you watch fencing, you'll see a lot of time is spent en garde, and trying to create opportunities to attack, including attacks on the blade.

To beat, or not to beat. That is the question.

This is a tough decision for a choreographer. If your beats are done well and make sense, then it enriches the choreography with strategic moves. It is more realistic to have attacks on the blade than not. It can build tension when beats fail, and it seems like there's no way to continue.

But how long will your audience endure actors circling each other, little beats and counter-beats with no real danger? Not long, I think. If you want a few tentative beats to raise the tension, that's fine. Then, go for one bigger successful one that leads to thrust-and-parry sequences.

Here's a good example of beats without going too far. Take this scene from The Great Race (1965):

Of course, this is from an era when sword fights on film were entirely based on sport fencing, and actors were routinely trained in fencing as an approach to stage combat. In this way, they understood the function of the beat.

Overcoming a Parry

I think there's a misconception among some people that a stronger attack will destroy a parry. Or, that once parried, a good strategy is to keep pushing against the parry so that if the defender weakens, the attacker can push through and continue the cut. How slow and ponderous would every fight be... imagine if that was a strategy within real sword fighting or even a theatrical convention: whoever attacked first would just press and press in the same position until one of them got tired. If the defender got tired first, they'd get cut. If the attacker tired first, they'd withdraw, preparing for their opponent to attack somewhere else and press in the same way.

No.... Fighters discovered in prehistory that with any weapon, if you are blocked or parried, the best thing to do is immediately abandon that attack. Whether your choice is to attack again to a different target or prepare to defend yourself against a counter attack are both viable tactics. Pressing into a parry is not. Especially with a sharp sword, a speedy attack to an open target will always win.

So don't focus on strength, but speed and precision. This fulfills both needs of stage combat: it's safer for actors, and it's also more realistic for real sword fights. And remember, your character doesn't need to hit the sword, but hit the opponent. The sword is in your way.

Challenge Yourself

Don't forget that the FDC Certification course begins on May 1, 2016. If you can devote three weeks to learning how to fight, a world of roles opens up to you: the action hero. Sword fighting, staff technique and unarmed fighting are all important to portraying a dynamic character. Actors who can believably fight get cast in the most fun roles, as heroes and villains. Take up the challenge to earn Fight Directors Canada Certification as an Actor-Combatant and put that skill on your resume.